On Thursday, Feb. 24, Russian military began an invasion of Ukraine that caused shock and outrage across the world. For Formula One, it cast the relationship of the Haas team with Dimitry Mazepin and title sponsor Uralkali in a different light. As various sports began banning Russian involvement and withdrawing from commercial relationships with Russian companies, Haas were in the paddock at preseason testing for the new F1 season. This is the story of how those intense early days of the season played out for the team, and how they have since put the pieces together to be challenging at the front of the midfield in the campaign’s first two races.

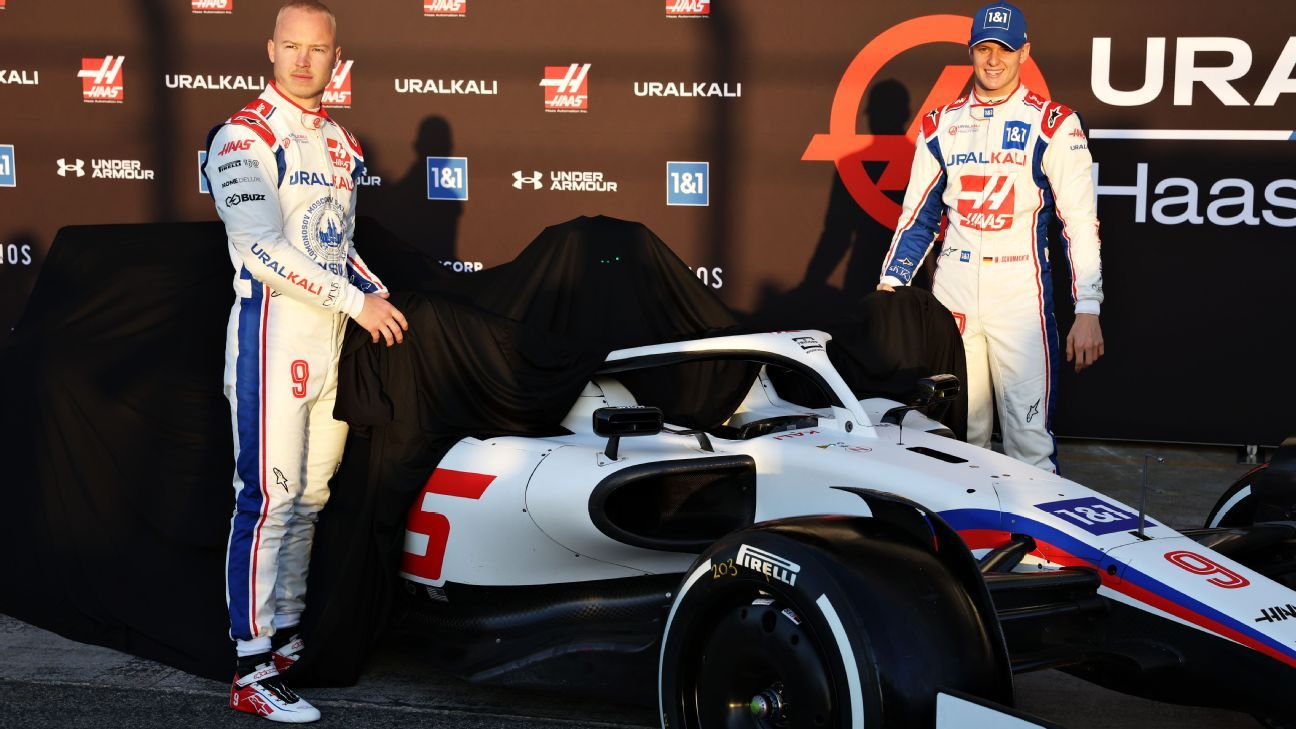

Over 2,500km away from Ukraine, images of the invasion by Russia were being played on all three of the wall-mounted TVs around the Haas team’s motorhome at the Circuit de Catalunya to the north-east of Barcelona. The small building, decked out in the red, blue and white of Uralkali, a major Russian chemical company, was at the end of a paddock hosting an F1 preseason which, by that point, felt irrelevant in the grand scheme of world events. Yet it was impossible to ignore a clear link between the two events.

Dmitry Mazepin, the man whose company had effectively saved Haas and kept the team in F1 at the start of 2021 by becoming its biggest financial backer, had started the week at the Barcelona circuit watching his son Nikita drive during a promotional filming day for the team. By Thursday, he was at the Kremlin meeting Russian president Vladimir Putin and a handful of other Russian business leaders.

The second day of F1’s test at the Barcelona circuit was no longer about the excitement around the early pace of the Ferrari nor which car design had caught the eye of the paddock’s tech journalists. It was all about Russia: about the race due to be held there in September and about Haas’ link with one of Russia’s most influential businessmen.

As Thursday progressed there remained no word from F1 or Haas about what it would do next — the Russian Grand Prix was not cancelled until Friday. Haas’ motorhome at the end of the paddock had become the focal point of the media’s attention. The team cancelled media sessions on the day as discussions continued behind the scenes.

Team owner Gene Haas and his F1 team boss Guenther Steiner had been at the circuit together when they saw the first news reports of the invasion, which had begun in the early hours of the morning, at 5am Spanish time. To Haas, it was immediately obvious what the ramifications would be for his F1 team.

“We had really good relations with Nikita and Uralkali,” Haas told ESPN in an interview in mid-March. “They were a great sponsor. They provided much needed capital.

“We really tried to make this thing work. But when you saw the media pictures of people just being bombed and shot at, this wasn’t going to work.”

Mazepin’s close relationship with Putin had never been a secret.

“It wasn’t an issue because there was no invasion of Ukraine at the time,” Steiner told ESPN. “We were well aware and there was no issue. Everything would be the same still if the invasion wouldn’t have happened. We couldn’t see forward one and a half years [when the deal was first signed], we are not this good.”

Haas’ discussions with Steiner became key to the decisions that followed. Netflix’s blockbuster series “Drive to Survive” has built an image of Steiner as a potty-mouthed and eccentric man who happens to be running an F1 team, but his no-nonsense attitude and habit for saying things exactly as they are are also traits that make him such a good team principal.

The fourth season of that Netflix show would come out two weeks later — by which point Haas had split with Uralkali and Mazepin completely — and showed Steiner at his best. One scene shows Steiner’s reaction to Mazepin spinning out at the second corner of his first F1 race with a “this is why people hate you,” while another showed Steiner telling his driver on no uncertain terms he had an identical car to teammate Mick Schumacher. The Mazepins felt this was not the case — one of the standout moments in the Haas episode is Dmitry threatening to pull funding if his son is not given a better car than Schumacher.

The dynamic was clearly complicated by Mazepin’s split interests: financier and father.

“I would call this normal for a father of a race car driver! Not for a sponsor,” Steiner told ESPN. “Fathers are normally very emotional about their kids. Do we not all wish the best for our kids? It’s the same for all of us. He wasn’t the easiest one to deal with.”

Nikita Mazepin’s time at Haas was complicated before he had even competed at a race. Prior to the season, the Russian driver shared a video on Instagram which showed him groping a woman in the back of a car, for which he would eventually apologise. His on-track results as a rookie were underwhelming. Although the team was comfortably last in the pecking order, he frequently failed to match Schumacher’s pace and developed a habit of spinning out of races.

Cutting the ties

At 7pm local time on Feb. 24, an hour after Thursday’s test had finished, a decision was made. Haas would remove all Uralkali branding from its car as well as the red, white and blue flashes that made the car resemble a Russian flag. Other team partners had made it clear during the day that they could not tolerate continuing alongside Uralkali’s brand. The decision came in the evening as Haas had been keen to talk with the board at Haas Automation, based in California.

“It was just ‘we have to stop this now and then deal with the consequences after,'” Steiner said. “In eight hours, you don’t find a conclusion for any of this. The time is not there. I think we reacted the right way.”

However, Mazepin would still drive in testing on Friday, as scheduled. Haas said he felt it was unfair on that day to punish the Russian driver for events beyond his control. Yet it would transpire that being in the car on Friday would only serve to reinforce to Mazepin the feeling that his F1 future would be unaffected by events in Ukraine and that his contract was completely separate to the one the team had with his father’s company.

“Call me naive, perhaps, but I didn’t really, truly feel that I or my seat was in any danger,” Mazepin told ESPN in an interview later.

Mazepin claims the last thing Steiner told him before he left the paddock on Friday (Feb. 25) was that the team had no intention of dropping him unless the FIA, motor racing’s governing body, banned Russian drivers from competing. He fully expected to be in Bahrain for F1’s second preseason test.

Steiner categorically denied Mazepin’s version of events. “I didn’t say that,” Steiner told ESPN. “At no stage did I say that.”

Eight days followed between Mazepin’s final laps in the car on Feb. 25 and the announcement on March 5 that the team was moving on from both driver and title sponsor. Mazepin called that period a “weird silence,” as he did not hear from Haas at any point on the team’s thinking.

Asked if he felt betrayed by Steiner or Haas, Mazepin said: “I obviously would love to live in a world where if you say something and have a trusting relationship, I’d love to sleep well on it knowing that I can trust.

“I think every dirty station can be handled in a better way. We are all humans, we’ve got an ability to speak. And I think it’s an important one to use.”

However, it is clear Mazepin did not contact Haas at any point after the Barcelona test for further clarification.

“It wasn’t like they [Mazepin and his team] were asking to stay in the car,” Haas told ESPN.

During that eight-day wait, Mazepin’s confidence had been strengthened further by motor racing’s governing body, the FIA, confirming it would allow Russian and Belarusian drivers to compete if they did so under a neutral flag and if they signed a waiver of political neutrality.

Haas had hoped the FIA would make their decision easier but as it turned out, another racing federation did in response to the FIA announcement. Motorsport UK announced it would ban Russian drivers from racing at the British Grand Prix. It was clear other racing federations could follow suit.

“Once the UK came out and banned Russian drivers, it’s kind of, the writing’s on the wall,” Haas told ESPN. “It’s not going to do us any good to sit there and have a Russian driver who can’t drive the car.”

Mazepin says he found out he had been dropped when the 50-word press release landed in his inbox that Saturday morning. Haas insist he was notified before then. How much time there was between the two messages is unclear.

Four days later, Mazepin’s name appeared alongside his father’s on a fresh list of sanctioned Russians.

“I truly was surprised to see myself there,” Mazepin told ESPN. “I think it’s fair to say that I understand why some people think I should be sanctions. But I don’t agree with it.

“I think it is the dark side of the cancel culture when you just wave that indiscriminately, rolling over everyone. I feel like there is no process. There is also no ability to think reasonably.”

For Haas, it vindicated the decision.

“It was really kind of out of our hands,” Haas told ESPN. “I think it was all pretty professional. And we all, I think both sides, felt it was it was kind of out of our control. We were not the ones that are in control.”

Mazepin was clearly hurt by the team’s decision, insisting his contract and the team’s deal with his father’s company were separate. While that may be true on paper, it is also true that one would not exist without the other: Like many “pay drivers” before him, Mazepin would not have been in F1 on pure talent alone.

To race under an FIA flag, he had to sign the declaration of neutrality — not a condemnation of Putin or the war, but also not an endorsement of it. In his interview with ESPN, he was offered three more opportunities to distance himself from the invasion and Putin, but he did not take any of them. He instead used each opportunity to talk about what he perceives as the unfairness of banning athletes of a certain nation from competing.

Mazepin has set up a foundation, We Compete As One, for Russian athletes who have been stopped from competing in sports because of the sanctions placed against the country right now.

“There was a time when athletes from conflicting nations would come together to compete,” he said in response to one of those questions. “And, you know, this was a really powerful message that they were putting aside differences and remembering that, at the end of the day, they’re all people.

“They’re all great athletes in their bodies and they can compete to one another. And I don’t see why people should be punished. I think they have a right. And I really want to respect that neutrality, right that men and women have, in general.”

Mazepin said he never had the chance to look at the neutrality waiver because the Haas announcement came so soon after he had been sent it by the FIA, but he has also never explicitly said he would have signed it in order to race in Formula One.

Recent laws passed in Russia threaten its citizens with 15 years in prison just for saying the military invasion of Ukraine is anything other than a “special operation.”

Return of the Mag

Haas did not start the process of recruiting a replacement for Mazepin until after the split was confirmed. Kevin Magnussen, who drove for Haas between 2018 and 2020, was the only person Steiner called.

When the call came in, Magnussen and his wife, Louise, now living in Copenhagen with their 1-year-old daughter Laura, were preparing to go on a trip to the Bahamas via Miami before going on to Sebring for a sports car race with Chip Ganassi.

Steiner told Magnussen he felt good about the competitiveness of the new car and that they wanted him to drive it again. Magnussen accepted immediately.

After hanging up, Magnussen turned to his wife, with a boyish grin on his face, and said: “I’ve done something stupid!”

Louise Magnussen took some convincing, having lived through F1’s demanding schedule before they were parents. She also saw how Magnussen had grown frustrated at F1 driving a string of uncompetitive race cars and wanted to make sure he wasn’t coming back to do so again.

The return would be a big change for Magnussen, too. His racing schedule in 2021 was nowhere near as grueling as a life on the road as an F1 driver. Before that call came in, Magnussen was relishing the role of an F1-driver-turned stay-at-home-racing-driver-dad.

“I was in a happy place when Guenther called me, a good place,” Magnussen would later tell the media about his mindset.

But it was too good an opportunity to turn down. Once Louise was on board, the comeback was on.

Fortunately, Steiner was right. The second test in Bahrain proved there was pace in the car. The prospect of Haas being a very competitive midfield outfit was suddenly real.

The beaming smile on Magnussen’s face never seemed to go away through the Bahrain test or the race weekend that followed. The day before the race, he provided one of the best feel-good visuals in F1’s recent history, placing Laura in the cockpit of the Haas car and grinning ear to ear next to Louise as they took pictures of her.

Magnussen’s return was better than anyone expected. He finished fifth at the Bahrain Grand Prix. Magnussen said he would have “called bulls—-” if Steiner had promised that during their phone call. A ninth place finish in Saudi Arabia followed — during the race Lewis Hamilton remarked over his radio how fast Haas was.

For the Mazepins, seeing Haas thrive in a car built largely with their financial backing is a bitter pill to swallow.

“Of course it hurts,” Nikita Mazepin told ESPN. “I would have loved the chance to prove myself in a competitive car and was waiting for that chance all of last season, only to have it taken away at the last minute.

“Year two was to be the real goal we were working toward. So all that slog and investment of both effort and money, did not lead to the opportunity to really show a result.”

Haas still faces an uncertain future

Despite the good vibes generated by Magnussen’s return and his first two results back in the car, there are still big questions about the team’s future. Haas was quick to downplay suggestions it could not survive without Uralkali and there have been no indications of impending financial doom without the Russian company.

It is clear the whole saga has changed Haas’ opinion on “pay drivers,” a common feature of F1 for smaller teams — bringing in a driver on financial considerations rather than on the basis of talent.

“Everybody thinks that we’re running out of money, but it’s about spending the right amount of money,” Haas told ESPN.

“We’re trying to work within these budgets. So, that’s probably where we overcompensated by having to [employ] pay drivers, but we won’t do that again.”

The Saudi Arabian Grand Prix offered a reminder that the team is still operating on a tightrope right now. Magnussen’s teammate Mick Schumacher crashed heavily in qualifying, incurring around $1 million of damage according to Steiner. Schumacher was unhurt but the team opted against having him race due to the rebuild job required and the fact that another crash in the race would risk crucial car parts needed to compete the Australian Grand Prix on Sunday.

Given the team’s track record, it’s likely there will be added scrutiny around Haas’ next choice of title partner. Uralkali is not the first company Haas has had to suddenly cut ties with. In 2018, the team signed a title sponsorship deal with Rich Energy, fronted by the erratic and eccentric William Storey, but the deal fell apart midway through the season amid missed payments

Asked if the team could learn lessons from both incidents, Steiner said: “You never say ‘I do not need to learn anything,’ but it was two completely different scenarios.

“The second one, a war was involved. I hope I don’t have that again in my life. I hope that for the world, not me personally. If you ever think you ended up in something like this… you would never. But all of a sudden we are in it. Lessons always will be learned.”

Whatever the next few months hold for Haas on and off the track, there should be no doubting the owner’s desire and willingness to stick to his F1 project.

When asked if all the hassle of the past few years and the costs involved in trying to be competitive in F1 is worth it, Gene Haas’ response was as clear as he could be.

“It will be worth it when we win a race.”

Additional reporting by Ryan McGee and Laurence Edmondson